Christophe Jacquet,

Chaumont 2013_6 (10 exemplaires)

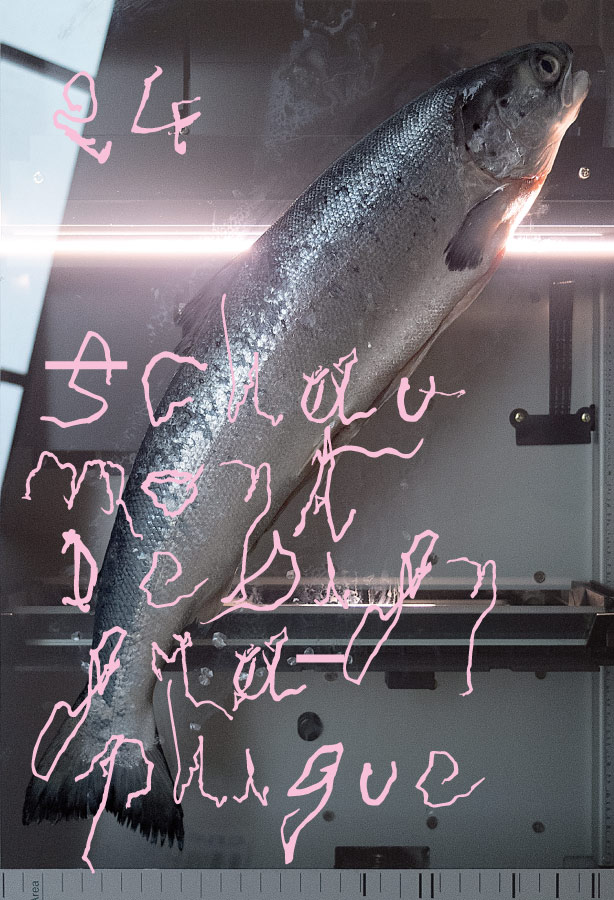

Que voit-on donc de si inconvenant sur la nouvelle affiche du Festival International de l’Affiche et du Graphisme de Chaumont confiée à Christophe Jacquet, il n’y a pas si longtemps dit Toffe ?

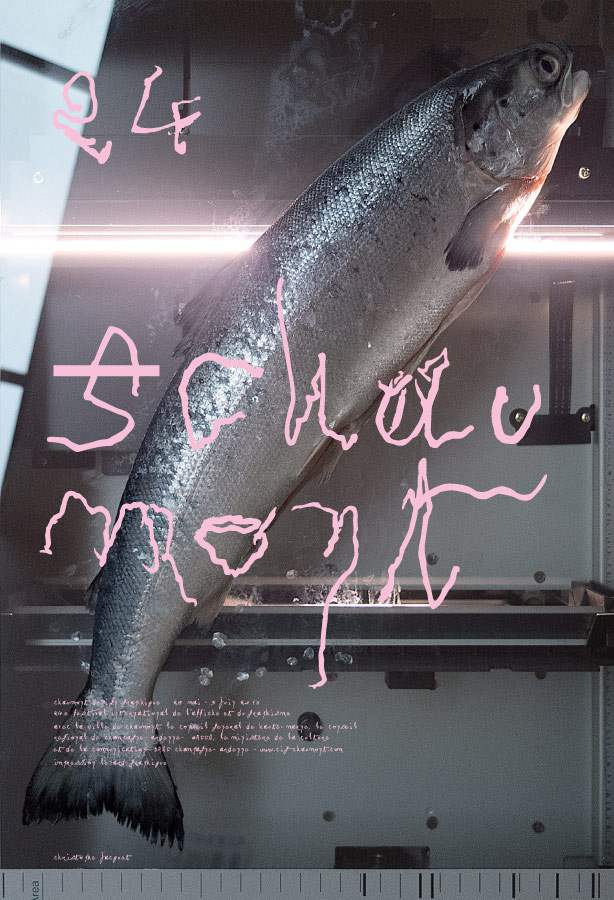

Une image à priori assez simple, la photographie frontale d’une bête : un bête poisson, bêtement posé sur un scanner, l’outil banal du graphiste et de tout environnement bureautique qui se respecte. Et puis une écriture, il est vrai assez étrange, mais proposée dans une configuration attendue, bien alignée, ferrée à gauche, comme on peut le dire entre spécialistes.

Évidemment, à y regarder de plus près, comme on se doit justement de le faire quand on est spécialiste, vaguement intéressé aux choses graphiques ou simplement doté de moyens intellectuels, les choses sont peut-être moins évidentes. On pourrait presque se risquer à dire que l’objet graphique se raffine.

Il y a d’abord une faute d’orthographe — ou un défaut d’élocution – qui vient s’assumer par une évidente biffure géométrisée — et peut-être officielle – pour jouer les calembours plus ou moins bons. Chaumont affublé d’un s initial — peut être à la façon allémanique — vient jouer les saumons, dur à dire. Un caviardage pour un poisson qui n’est pas n’importe quel produit de poissonnerie. Un poisson qui, comme l’anguille — autre habituée des profondeurs et du répertoire graphique de Christophe Jacquet – nage entre deux eaux : en eaux troubles, douces et salées. Un beau et grand poisson à la robe irisée qui est aussi le produit le plus abordable des étals de pêcherie : un genre de luxe pour tous. Un poisson métaphorique dont la silhouette fut un temps associée aux briques fuselées d’alliage plomb-étain-antimoine destinées à alimenter les fonderies de l’industrie de la typographie.

Il y a aussi ce scanner pris en plongée et en flagrant délit de captation et de révélation. Un instrument de vision qui se fait vitre d’aquarium, surface d’inscription et milieu de vie des signes fluides. Un balayage lumineux qui peut faire surgir de ces potentiels obscurs qui agitent les tréfonds sédimentaires — calcaires marins ou marnes fluviales – la « montée de rose » de la chair des figures de discours.

Il y a enfin — un enfin entendu d’abord en termes de finalité – des écritures qui viennent ancrer la dérive des flux de significations de l’image en la mettant au service d’un discours explicite au sujet du vingt-quatrième festival d’un domaine de l’affiche élargi au graphisme. Une grande écriture de démonstration, rosée et pourtant âpre, qui se déploie en écho contrarié au balayage du scanner. Un texte heurté et chantourné, difficile à décrypter, peut être une calligraphie, que Christophe Jacquet persiste à qualifier comme typographie. Une typographie atypique, une graphie anormale : une grotesque grotesque. Une dés-écriture de prélèvement, extraite du carnet des derniers efforts de communication d’une personne qui perd et sa graphie et sa vie : pas une écriture des commencements, une écriture gérée dégénérée de la finitude, une fin de l’écriture.

Il y aura donc enfin un discours de la finitude : fin des écritures, fin des images. Ce beau poisson brillant tendu au ventre fendu rose et humide, ce surgissement vital vaguement sexuel dans l’espace autre à la fois de l’image et de la mer est à la fin un poisson mort. Une bête morte sur un scanner de représentation. Une nature morte dont l’histoire nous fait remonter peut être avec humour aux maîtres hollandais dont l’actualité du graphisme regorge. Une vanité qui inscrit le graphisme dans l’histoire longue de la réflexion des images. Vanité du trophée, vanité des apparences, vanité du discours intéressé des fétiches de la marchandise ou de l’image de propagande et en même temps, persistance mystérieuse et manifeste de la magie d’une image qui échappe toujours, comme l’écaille glissante du poisson.

« C’est moi qui ai tout fait mais j’ai tout pris. Le poisson c’est un poisson d’élevage. Le scan c’est Epson. L’écriture, je sais qui l’a faite ». Chez Christophe Jacquet, le graphisme relève du symptôme urgent, de cette forme d’angoisse qui, pour la clinique psychanalytique, est le signal vivant du réel : une empreinte et un emprunt documentaires, au plus près des choses ; des présences, des matières brutes brutalement prélevées. Un index, un indice, qui indique ou induit, qui tente avec le matériau impropre du langage d’atteindre le réel.

Christophe Jacquet développe un discours du service des images qui suit un fonctionnalisme peut-être paradoxal. L’affiche veut servir au mieux le discours symbolique littéral qu’elle supporte parce que, comme la réalité elle-même, elle lui résiste à la fin. Résister à la fin, beau programme.

Thierry Chancogne.

Christophe Jacquet,

Chaumont 2013_5 (10 exemplaires)

What is it that is so improper about the new poster for the International Poster and Graphic Design Festival of Chaumont, commissioned from Christophe Jacquet, not so long ago a.k.a. Toffe?

An apparently straightforward image, a full-on photograph of an animal: a mere fish, placed simply on a scanner, that mundane tool of graphic designers and of any self-respecting office environment. And then there’s the writing – quite odd writing, it has to be said, but proposed in an unsurprising configuration, well aligned, flush left, as specialists sometimes say entre eux.Obviously, when you take a closer look, which is what you are duty-bound to do when you are a specialist, with a vague interest in graphics or merely endowed with intellectual resources, things are perhaps less obvious. You might even go so far as to say that this graphic piece gains in refinement.

Firstly, there is a spelling mistake – or a speech defect – which is affirmed by a clear geometric (and perhaps official) strike-out, so as to venture a pun of questionable quality. Chaumont, enhanced by an initial s, perhaps in the German manner, sounds rather like saumon (salmon): a linguistic leap. And with a caviardage1 for a fish that is not your typical fishmonger’s product. A fish which, like the eel – another denizen of the deep, and of Christophe Jacquet’s graphic repertoire – swims between fresh and salt waters, both of them murky. A large, handsome, iridescent fish that is also the most affordable product at fish-market stalls: a kind of luxury for all. A metaphorical fish whose outline was once associated with the slender lead-tin-antimony alloy ingots, known as saumons, supplied to French type foundries.

There is also the scanner, shot top-down, and caught in the act of capturing and revealing. A viewing instrument that turns into an aquarium’s glass pane, an inscriptive surface, and a habitat for fluid signs. A light-sweep able to summon forth from the dark potentials stirring the sedimentary depths – marine chalk or river marl – the “rising pinkness” of the message’s figures.

And finally, there are writings that anchor the drifting flow of the image’s meanings by enlisting it to serve an explicit message about the twenty-fourth festival of a field expanded from posters to graphic design. Large demonstrative writing, pink yet pungent, which spreads out in a thwarted echo of the scanner’s sweep. A jerky, jig-sawed text, hard to decipher, possibly calligraphic, that Christophe Jacquet persists in calling a typeface. An atypical typeface, an abnormal script: a grotesque grotesque. A de-writing sample, taken from the notepad of the final efforts at communication by a person who is losing his words and his life: not written beginnings, but a degenerate script of finiteness; an end of writing.There is thus, lastly, a message of finiteness: the end of writings, and of images. This handsome glossy stretched-out fish with its wet split pink belly, this vital and vaguely sexual springing into the other space of both image and sea, is, at the end of the day, a dead fish. A dead animal on a display scanner. A still life whose story perhaps calls humorously to mind the Dutch masters, which currently abound in graphic design. A vanity that places graphic design within the long history of reflections on/of images. A vanity about trophies and appearances. A vanity about the self-interested discourse of the idols of commodities or propaganda images; and, at the same time, about the mysterious and manifest persistence of the magic of an image that always escapes, like a fish’s slippery scales.

“I did everything, but I took everything. The fish was farmed. The scan’s by Epson. And I know who did the script.” For Christophe Jacquet, graphic design is an urgent symptom, stemming from that form of anxiety which, in a psychoanalysis clinic, is the living signal of reality: a documentary imprint and borrowing, very close up to things, to presences, to raw materials roughly sampled. A pointer, an index, which indicates or induces; which, with the improper material of language, attempts to touch reality.Christophe Jacquet develops an image-serving discourse that follows a perhaps paradoxical functionalism. The poster wants to best serve the literal symbolic message that it underpins because, like reality itself, the poster resists its purpose. Resisting one’s purpose: an appealing agenda indeed.

Thierry Chancogne.

Christophe Jacquet,

Chaumont 2013_4 (10 exemplaires)

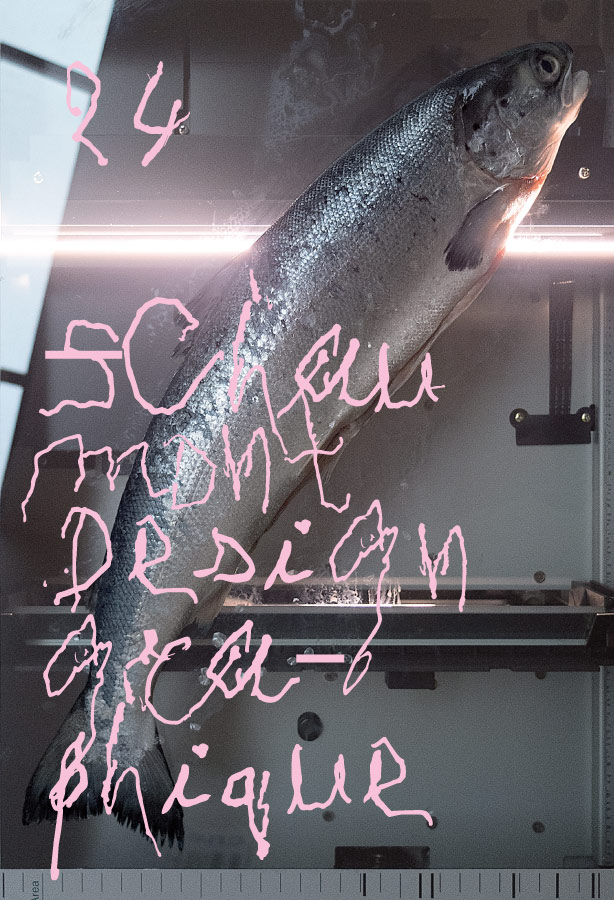

L’affiche du dernier festival international de Chaumont est belle comme la rencontre apparemment fortuite sur la vitre d’un scanner d’un saumon et d’une lettre mal tracée. La crudité presque obscène du salmonidé, dont le mucus et les écailles souillent la feuille de verre du scanner, rivalise avec la maladresse – elle aussi presque obscène – de la graphie. Ces deux niveaux de l’affiche sont noués par une double ligature sémantique : un jeu de mots et la couleur rose (liant la chair visible de l’écriture – sa graisse – à la chair invisible du poisson). On pourrait en rester là ou continuer à se délecter visuellement en notant la redondance intentionnelle entre la peau luisante du poisson et le brillant du vernis UV qui recouvre l’affiche, comme s’il s’agissait paradoxalement à la fois d’étendre l’éclat poisseux de la bête à l’ensemble de l’affiche et de nous protéger de manière imaginaire de la puanteur proverbiale de cette dernière par un film transparent. Mais la chose va plus loin et demande si on veut en mesurer réellement l’intérêt que l’on s’aventure sur un terrain peu pratiquée par la critique de design graphique. La couleur rose de l’écriture désordonnée qui s’étale sur l’affiche n’est pas gratuite ou purement esthétique puisqu’elle exemplifie, comme on l’a déjà suggéré, la couleur de l’intérieur du poisson sur fond duquel elle se détache. Mais il y a plus. Cette couleur rose s’ajoutant au motif matériel du poisson et à l’instrument du scanner fonctionne comme indice de l’auteur du délit (dont le rose est l’une des couleurs de prédilection). La rencontre entre ces trois éléments manifestes ou perceptuellement saillants sera, pour les regardeurs informés qui se bousculent dans les allées du festival de Chaumont, tout sauf fortuite en leur permettant d’en reconnaître l’auteur avant d’en lire sur l’affiche la signature.

Un scanner, un poisson, la couleur rose, cette accumulation des indices du signataire est elle-même l’indice de quelque chose. Peut-être d’une volonté de faire le point ou même de faire le deuil d’une pratique antérieure. Le lieu commun de la vanité introduit par le poisson mort s’en trouve comme personnalisé. Un peintre qui veut peindre intentionnellement ses derniers tableaux (les images dans lesquelles il pourrait, comme l’aurait dit emphatiquement le premier-ministre-de-la-culture, « regarder son visage de mort ») fera un autoportrait, mais que peut faire un artiste graphique, constamment aux prises avec la commande, qui veut produire intentionnellement ses dernières affiches ? Notons que le poisson s’offre ici doublement comme un symbole évident de l’artiste selon une rhétorique iconique du « portrait en… »2 et selon une rhétorique de l’association verbale – le motif de l’« ichthus » étant associé historiquement au pré-nom d’artiste de l’auteur3. Toute surinterprétation écartée, la mise en abyme de son dispositif de travail antérieur via la photographie suggère que l’artiste prend du recul, se déplace, et donnant à voir l’autre flanc de la bête, se retourne sur son activité passée4. La roublardise de vieux professionnel avec laquelle il s’acquitte parfaitement de sa commande par un jeu de mots vaseux (qui ne tient qu’au choix du poisson), pour pouvoir se livrer tout entier à sa méditation personnelle a par ailleurs quelque chose de réjouissant.

Jusqu’ici je n’ai fait que considĂ©rer certaines propriĂ©tĂ©s manifestes comme indices de contenus non manifestes ou suggĂ©rĂ©s. Mais le tour des propriĂ©tĂ©s manifestes une fois fait, que reste-t-il ? Ici il faut se dĂ©barrasser de l’illusion de l’autonomie sĂ©mantique de nos Ă©noncĂ©s. Que veut dire une mère qui dit littĂ©ralement Ă son enfant qui pleure de façon hystĂ©rique parce qu’il s’est fait une petite blessure : « tu ne vas pas mourir ». Certainement pas qu’il ne va pas mourir (quelle mère pourrait dire honnĂŞtement cela Ă son enfant…). Elle veut probablement lui dire : « tu ne vas pas mourir, aujourd’hui, de cette blessure ». Mais ceci implique qu’une partie de son Ă©nonciation n’est pas articulĂ©e dans l’énoncĂ© qui lui sert de vĂ©hicule.

Dire que nous devons prendre en considération les propriétés non manifestes d’un énoncé pour accéder à sa signification, c’est rappeler que le contexte est cofacteur du contenu d’une énonciation. C’est une propriété non manifeste de l’énoncé « tu ne vas pas mourir » dans l’exemple que nous avons donné d’être prononcé en réponse aux pleurs stridents d’un enfant. Et c’est cette propriété non manifeste qui nous permet d’accéder à son sens réel. Ainsi la propriété la plus importante à connaître pour apprécier pleinement notre œuvre graphique n’est pas perceptuellement saillante. Il s’agit de la propriété de sa lettre d’avoir été générée à partir de l’écriture d’une personne qui, aux derniers instants de sa vie, était en train de perdre ses moyens intellectuels et luttait pour tracer ses derniers mots.

Ce fait ne saurait être évidemment indifférent à l’interprétation que nous donnons de l’affiche. D’autant que nous avions conclu précédemment sur la base d’indices indépendants que l’auteur y cherchait peut-être à produire l’une de ses dernières affiches.

Or, vous ne pouvez pas déduire ce fait de la simple appréhension de l’affiche. Il faut que vous l’appreniez d’une source extérieure à celle-ci. Après tout, la graphie maladroite qui s’étale ici pourrait également être, par exemple, le fruit d’une expérimentation hasardeuse : celle d’un Christophe Jacquet imbibé d’alcool s’essayant à écrire de la main droite. Observez comme cela changerait votre « perception » de la chose : un certain pathos laisserait la place à un exhibitionnisme potache. L’affiche produite dans ces circonstances imaginaires aurait pu être parfaitement indiscernable de l’affiche que nous avons devant les yeux, c’est-à -dire qu’elle aurait pu posséder exactement les mêmes propriétés perceptuellement saillantes, elle n’aurait pas été la même affiche5. Ce sont les propriétés perceptuellement non saillantes qui font souvent la différence dans l’art dit contemporain entre les œuvres pertinentes et les œuvres anecdotiques. Pourquoi n’en serait-il pas de même dans l’art graphique contemporain ?

D’abord, dans les circonstances imaginées, Christophe Jacquet n’aurait pas pu prétendre que les lettres utilisées relevaient d’une typographie puisque le texte de l’affiche aurait été directement manuscrit. Le fait d’utiliser l’écriture d’une personne défunte qui n’a évidemment jamais tracé les lettres « schaumont » sur un support6 obligeait à en tirer, après numérisation, des éléments ré-agencables qui constitueraient, au moins d’un point de vue fonctionnel, une typographie.

La considération attentive de ces lettres maladroites permettrait sans doute de tirer quelques enseignements sur l’alphabet latin comme schéma notationnel et sur le seuil de lisibilité mutuelle de ses lettres en fonction des deux réquisits syntaxiques qui ont été mis en avant par Nelson Goodman : la disjonction de caractères et la différenciation finie ou articulation (le chapitre IV de Langages de l’art contenant entre autres, pour qui sait le lire, une sorte de traité de typographie métaphysique…). Mais il ne s’agit pas ici de simplement jouer le schéma notationnel de l’alphabet latin comme méta-norme laxiste contre tous les carcans dogmatiques des normes typographiques.

Car, la personne défunte qui hante cette affiche avait certainement appris à tracer parfaitement une cursive sur un tableau noir. Or, même si ces derniers efforts sont loin de cette norme, ils restent avec un peu de patience et d’astuce, lisibles. Si vous croyez que la signification n’est affaire que de systèmes, de normes ou de codes, demandez-vous, comme l’a fait un jour le philosophe Donald Davidson, pourquoi des énoncés mal formés nous permettent souvent de nous faire comprendre.

Il est beau que l’énonciation graphique dont l’affiche du festival international de l’affiche et du graphisme de Chaumont est le véhicule, nous rappelle ainsi que ce que quelqu’un nous montre excède toujours ce que nous voyons, de même que ce que quelqu’un nous dit excède les mots que nous entendons ou que nous lisons. Nous utilisons des énoncés pour parler, mais nos énoncés ne parlent pas à notre place. Comme les lettres utilisées par une mère pour s’adresser à son fils ou celles qu’un fils utilise en retour pour s’adresser à sa mère.

Frédéric Wecker

Christophe Jacquet,

Chaumont 2013_4 (20 exemplaires)

The poster for the most recent International Festival of Chaumont has the beauty of an apparently chance encounter on a scanner pane between a salmon and a badly-drawn typeface. The quasi-obscene rawness of the fish, its slime and scales soiling the scanner’s glass pane, vie with the (also quasi-obscene) clumsiness of the script. These two levels are tied by a dual semantic ligature: a play on words and the colour pink (linking the visible flesh of the writing – its fat – to the invisible flesh of the fish). We could stop there, or continue to visually savour the piece, by noting the deliberate redundancy between the fish’s shiny skin and the gloss of the UV varnish covering the poster, as if the idea was, paradoxically, to extend the animal’s sticky shimmer to the entire poster and protect us, in an imaginary way, with a transparent film from the poster’s proverbial stench. But the poster goes further and asks us, should we really want to measure its significance, to venture into a field rarely visited by graphic-design criticism. The pinkness of the disorderly script that spreads across the poster is not gratuitous or purely aesthetic: it exemplifies, as suggested above, the colour of the inside of the fish, against which it stands out. But there’s more. This pinkness, added to the material motif of the fish and to the instrument that is the scanner, operates as an clue to the author of the crime (one of whose favourite colours is pink). The meeting of these three manifest or perceptually salient elements will, for the informed beholders jostling in the Chaumont Festival aisles, be anything but fortuitous, enabling them to recognise the author even before they see his signature on the poster.

A scanner, a fish, the colour pink: this accumulation of clues to the signatory is itself a clue to something. Perhaps to the desire to take stock of a previous practice, or even to achieve closure from it. The commonplace of the vanity introduced by the dead fish thus feels personalised. A painter who wants to intentionally paint his final pictures (the images in which he could, as France’s first minister of culture would grandiloquently have put it, “see his dead man’s face”) will make a self-portrait; but when a graphic artist, constantly grappling with commissions, wants to intentionally produce his final posters, what can he do? We should note that the fish is doubly offered: as an obvious symbol of the artist according to an iconic rhetoric of the “portrait as…”((If you find the idea of the artist portraying himself as a dead fish grotesque, remember that the artist Erwin Wurm is well known for his self-portraits as a gherkin.)) and to a rhetoric of word association – the motif of the “ichthus” being historically associated with the artist’s (non-Christian) name used by the author7. Avoiding any over-interpretation, the mise en abyme of his previous modus operandi through the photograph suggests that the artist is standing back, moving, and, in showing the animal’s other side, contemplating his past activity8. Indeed there is something uplifting about the old pro’s artfulness with which he perfectly fulfils his commission using a lousy pun (which depends solely on the choice of fish) so he can fully devote himself to his personal meditation.

So far, I have only considered certain manifest properties as clues to non-manifest or suggested content. But once the review of manifest properties is complete, what is left? Here we must rid ourselves of the illusion that our utterances are semantically self-contained. What does a mother mean when she literally says to her child, who is crying hysterically because he has slightly injured himself, “You’re not going to die”? Certainly not that he is not going to die (what mother could honestly say that to her child…). She probably means “You’re not going to die, today, from this injury”. But this implies that part of her utterance is not articulated in the utterance that serves as the vehicle.

To say that we must consider the non-manifest properties of an utterance in order to access its meaning is to give a reminder that context is a co-factor in the content of an utterance. In the above example, what is said in reply to a child’s shrill crying is a non-manifest property of the utterance “You’re not going to die”. And it is this non-manifest property that gives access to its actual meaning. Accordingly, to fully appreciate the graphic artwork in question, its most important property is not perceptually salient. It is the script’s property of having been generated from the writing of a person who, in the final moments of his life, was losing his intellectual resources and fighting to record his last words.

This fact must clearly be related to how we interpret the poster – especially as we had previously concluded, on the basis of independent clues, that the author was perhaps seeking to produce one of his final posters.

Now, this cannot be deduced simply by beholding the poster. You must learn it from an outside source. After all, the clumsy writing that stretches out here could also be the result, for example, of a rash experiment: a sozzled Christophe Jacquet trying to write with his right hand. See how that would change your “perception” of the piece: a certain pathos would give way to schoolboy showing-off. The poster produced in these imaginary circumstances would have been utterly indistinguishable from the poster before our eyes: it could have possessed precisely the same perceptually salient properties, but it would not have been the same poster9. The perceptually non-salient properties are often those which, in so-called contemporary art, set relevant works apart from trivial ones. Why should this not also apply to contemporary graphic art?

Firstly, in our imagined circumstances, Christophe Jacquet could not have claimed that his letters were from a typeface, because the poster’s text would have been directly handwritten. Using the writing of a dead person who has clearly never drawn the letters “schaumont” on a substrate10 required him to extract from it, after digitisation, rearrangeable elements that would constitute a typeface, at least functionally speaking.

Attentive consideration of these awkward letters would doubtless teach us a few things about the Latin alphabet as a notation system, and about the threshold of mutual legibility of its letters as per the two syntactic requirements highlighted by Nelson Goodman: the disjointness of the characters, and finite differentiation or articulation (chapter IV of Languages of Art contains among other things, for those able to interpret it, a sort of metaphysical treatise on typography…). But my intention here is not simply to play the notation system of the Latin alphabet as a lax meta-norm off against all the dogmatic shackles of typographic norms.

The dead man who haunts this poster had definitely learned how to do joined-up handwriting on a blackboard. And although these final efforts are a far cry from this norm, they are, with a little patience and cleverness, still legible. If you believe that meaning is only to do with systems, norms and codes, then ask yourself, as the philosopher Donald Davidson one day did, why we can often make ourselves understood with ill-formed utterances.

It is a fine thing that the graphic enunciation conveyed by the poster of the International Poster and Graphic Design Festival of Chaumont reminds us that what someone shows us always exceeds what we see – just as what someone tells us exceeds the words that we hear or read. We use utterances to speak, but our utterances do not speak in our stead. Nor do the letters that a mother uses to address her son, or those that her son uses in reply.Frédéric Wecker

Christophe Jacquet,

Chaumont 2013_3 (20 exemplaires)

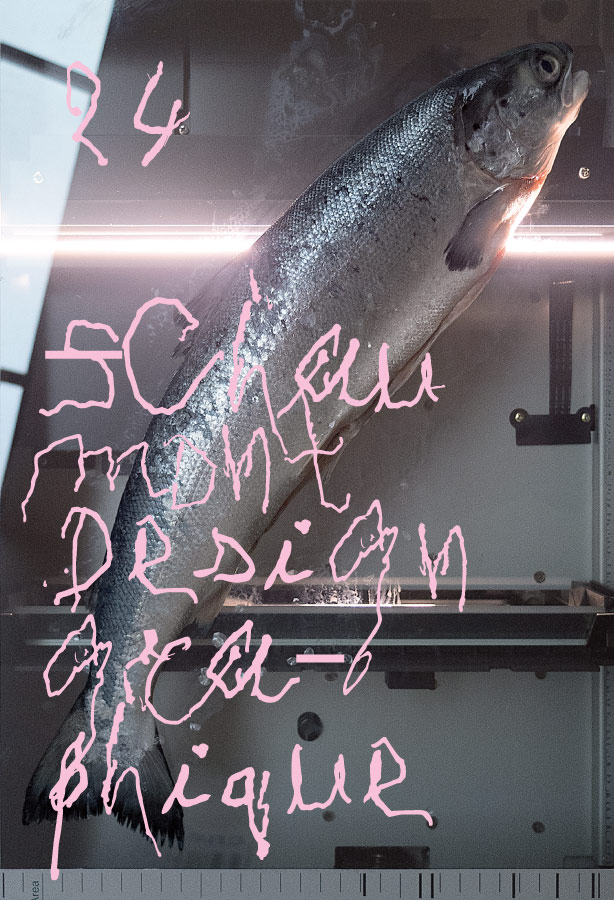

Christophe Jacquet pose la situation implacablement : 50/50. Comprenez qu’il exigera autant de son commanditaire que celui-ci attend de lui. Le deal est honorable. Pas tant Ă cause de la loi des chiffres ronds que par ce rappel simple que l’affiche ne vaudra que si elle est bien portĂ©e, haut et fort. Il n’est pas question du rĂ´le du commanditaire auprès du graphiste, Christophe n’a pas besoin d’aide, mais vis-Ă -vis de l’affiche. RĂ©soudre la nĂ©cessitĂ© de se mettre dans une image aussi fortement signĂ©e, du sceau de son auteur et du caractère propre de cette affiche. L’exigence originelle de Christophe en provoque d’autres. En tant que commanditaire j’attends que le graphiste nourrisse le sujet que je pose entre nous autant que j’ai pu le faire Ă travers une programmation, Ă travers – prĂ©cisĂ©ment – le choix de ce graphiste. J’attends qu’il fasse plus et mieux que « donner Ă voir », la vilaine expression qui pousse Ă recevoir l’affiche en spectateur. J’attends, et Christophe Jacquet m’en convainc, qu’elle rende actif par le regard. Que la rĂ©ception soit rĂ©-action.

Si je regarde ici l’affiche, je souris de satisfaction à la voir, sans tergiversation, convoquer dans son ascendance le champ entier de l’image par une parenté à ces natures mortes flamandes si aptes à enflammer l’œil. Parenté aussi avec l’inconscient visuel collectif construit à grands pans de quotidien. Le cadre est donné qui, par son échelle, évite et pointe nombre des pièges qui menace un Festival de graphisme et d’affiches dans sa programmation comme dans sa communication. C’est précisément ce dernier terme qui est interrogé par notre affiche. La communication n’est pas suspecte en soi, mais les usages galvaudent parfois les mots et les idées. Pour cette affiche, un terme s’avère plus exact : l’expression du Festival. Je passe rapidement sur le fait que les registres les plus explicitement graphiques : géométrie, formes en aplat, trames dont Christophe est pourtant un adepte, typographie… ne sont pas convoqués. L’opération relèverait davantage du strict exercice texte image. Mais, serait-ce la viscosité du poisson, cette impression échappe tant le texte et l’image obéissent à des raisons impérieusement différentes. Avec l’écriture, Christophe, parce qu’il est entier, embrasse tout le champ de l’expression humaine, depuis l’individu jusqu’à l’institution. C’est bien le paradoxe, vital, de ces dernières de confier à un seul homme l’expression de leur pluralité. À charge pour une lecture d’opérer ensuite en lieu et place des automatismes usés par la publicité. Quant à l’image, fort bien commentée dans les pages qui suivent, je ne parlerai pas de la forme mais des mécaniques à l’œuvre. Plus que le jeu d’échelle sur l’objet du poisson et l’image même, c’est la logique du déplacement qui opère. Déplacement des pratiques et des statuts, déplacement de pans entier du territoire visuel. Le raisonnement par l’abrupt.

Étienne Hervy

Christophe Jacquet,

Chaumont 2013_2 (20 exemplaires)

Christophe Jacquet sets out his terms implacably: 50/50. Meaning that he will demand as much from his client as his client expects from him. It’s an honourable deal. Less for the numbers’ convenient suppleness than for its simple reminder that a poster will only be worthwhile if it is wholeheartedly and elegantly borne. At issue here is the client’s role: not vis-à -vis the designer – for Christophe needs no help – but in relation to the poster. The client must resolve the necessity of buying into an image of such powerful signs: its author’s seal and the poster’s own character. Christophe’s initial requirement gives rise to others. As a client, I expect the graphic designer to nourish the subject11 place between us as much as I have done through the programme – and by choosing a particular designer. I expect him to do more and better than “donner à voir”,1 the nasty expression that has you receive the poster as a spectator. I expect – and Christophe Jacquet has convinced me here – that the gaze will render it active; that reception is re-action.

If I look here at the poster, I smile with satisfaction to see it so readily conjure in its ancestry the whole realm of imagery, through a kinship with those Flemish still-lifes that so ably set the eye ablaze. Through a kinship, too, with the collective visual subconscious constructed by great swathes of the everyday. The poster is thus framed: and the frame, in its scale, avoids and pinpoints a number of pitfalls that threaten a poster and graphic-design festival’s programme and communication. The latter term is precisely what our poster explores. Communication is not inherently suspect, but its uses sometimes demean words and ideas. With this poster, another term is more accurate: the Festival’s expression. I will note only briefly that the most explicitly graphic registers – geometry, flat forms, screens (which Christophe is keen on), typography, etc. – are not employed here. The piece appears to be more of a strict text-and-image exercise. But this impression slips away – because of the fish’s stickiness, perhaps – because text and image are working to such categorically different agendas. With the script, Christophe, an uncompromising character, embraces the entire field of human expression, from individual to institution. Here is the crucial paradox: institutions task a single man to express their plurality. A reading must then be conducted, instead of the reflexes tweaked by advertising. As for the image, which is given a very fine commentary in the following pages, I will speak not of its form but of the mechanics at work. What is operative here, more than scale-play with the fish and the image itself, is the logic of displacement. Displacement of practices and statuses; displacement of whole expanses of the visual territory. An abrupt reasoning.

Étienne Hervy

Christophe Jacquet,

Chaumont 2013_1 (300 exemplaires)

- Journalistic slang to describe the redacting of passages in an article or document by means of black marks (as if with caviar), coined in the 19th century in reference to the highly censorious regime of Russian Czar Nicholas I – Translator’s note. [↩]

- Si l’idĂ©e d’un autoportrait de l’artiste en poisson mort vous paraĂ®t grotesque, souvenez-vous que l’artiste Erwin Wurm est bien connu pour ses autoportraits en cornichon. [↩]

- L’ichthus auquel il est ici fait rĂ©fĂ©rence (et dont le symbole du poisson est le raccourci graphique – « ichthus » est le mot grec pour poisson) est Ă©videmment l’acrostiche qu’utilisaient les premiers chrĂ©tiens – acrostiche dont la deuxième lettre est l’initiale du Nom que l’artiste avait raturĂ© dans son prĂ©nom pour fabriquer le nom d’artiste sous lequel il s’est longtemps fait connaĂ®tre (Christ-tophe). [↩]

- On comprend que le fond iconographique de l’affiche aurait Ă©tĂ© prĂ©cĂ©demment le scan du poisson et non pas la photographie du poisson en train d’être scannĂ©. [↩]

- On aura reconnu ici bien Ă©videmment la stratĂ©gie philosophique principale du roi de la critique d’art (le roi Arthur…). [↩]

- MĂŞme s’il fait partie du charme Ă©trange et glaçant de cette proposition graphique, une fois connu le fait contextuel principal, de suggĂ©rer la fiction que la faute d’orthographe affectant le nom de la ville serait due Ă la mĂŞme affection que celle expliquant le tremblĂ© des lettres. [↩]

- The ichthus referred to here (and for which the fish symbol is the graphic shortcut – ichthus being the Greek word for fish) is obviously the acrostic used by the first Christians; an acrostic whose second letter is the initial of the Name that the artist had struck from his first (or Christian) name to form the artist’s name by which he was long known (

Christ-tophe). [↩] - The pictorial background of the poster would, we gather, previously have been the scan of the fish and not the photograph of the fish being scanned. [↩]

- This is easily recognisable, of course, as the main philosophical strategy of the king of art criticism (King Arthur…). [↩]

- Although part of this graphic proposition’s strange and chilling charm is that, once the main contextual detail is known, it suggests the fiction that the spelling mistake affecting the town’s name could have the same cause as the shakiness of the lettering. [↩]

- Literally “give to see”; show, display – Translator’s note. [↩]