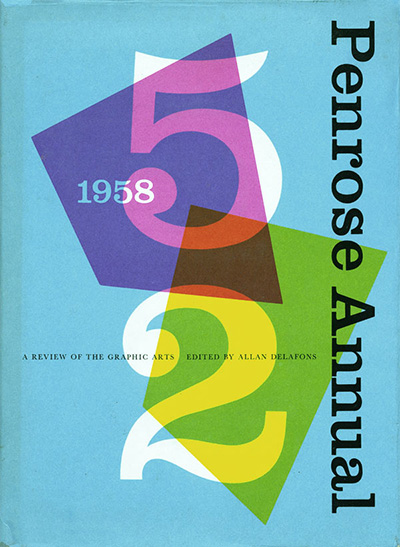

Published for the first time in 1958 in the 52nd issue of the Penrose Annual (A review of the graphic arts), James MoranŌĆÖs article is an introductory overview of the early years of the typography rendezvous known today as Les Rencontres de Lure, that still takes place each summer in Lurs-en-Provence (France) until this day. This article helps to shed light on the first years of this school of thought and on its role as an up-and-coming event that would gain importance as one of the main international places for type experimentation and critique at the dawn of the 1960s. Moran’s overview contributes to mapping out the circulation of ideas that existed between some of the major figures concerned with typography during the mid-twentieth century, including practitioners and historians (such as Blanchard, Dreyfus, Excoffon, Frutiger, Novarese, Vox, ZapfŌĆ”) but also authors and artists (such as Giono, Ionesco, VasarelyŌĆ”). The article’s emphasis on the influence of the ├ēcole de Lure’s questionings on the way in which we approach writing, language and forms (that are still relevant today though certain points of view of that time are, at the very least, culturally and politically questionable) is a nice reminder of the importance of this lively┬ĀŌĆö and quite hedonist┬ĀŌĆö gathering that celebrates the culture of type.

{AB}

Lurs-en-Provence is a tiny village in the south of France, still mediaeval in appearance and difficult of access. It has been for the past five years the annual meeting place of a group of people connected with printing and its allied professions, basically French, but with representatives from other countries attending from time to time. For a week each year they have discussed aspects of the graphic arts with an emphasis on typography.

This gathering, known as LŌĆÖ├ēcole de Lure (Lure is a nearby mountain), held in savagely beautiful surroundings, in conditions which would not be acceptable to some fastidious English people, has not only gained a wide reputation but is exerting an influence which would seem to be completely out of proportion to its size and organization.

The whole thing is a paradox. Because this handful of people meet in Lurs typefoundries all over the world are changing their specimen books. Because of their discussions the Roman alphabet could become the basis of world education. Because they have encountered contradictions of printing terminology our very language may be modified.

To attempt to explain this it is necessary to begin at the beginning. The beginning is a man called Maximilien Vox, who is and has been many things┬ĀŌĆö publisher, author, translator, designer, typographer, and artist ŌĆö and creator of the annual Caract├©re N├Čel, showpiece of the French graphic arts, a specially bound copy of which was last year accepted by the President of the Republic (a novelty in protocol if not in history).

Vox is devoted to the graphic arts, particularly to the Roman alphabet which he sees as an outward manifestation of Greco-Roman-European civilization and the basis of a new renascence. He and a friend, the author Jean Giono, conceived the idea of using the little known village of Lurs as the setting for an annual rendezvous where printers, artists, designers, and photographers would discuss the problems of the new era in printing in an atmosphere and in a manner far removed from the official convention with its receptions, its formal functions, and its set speeches and programme.

So with Jean Garcia, typographer and graphic artist, and Robert Ranc, director of the Paris printing school Coll├©ge Estienne, Vox founded LŌĆÖ├ēcole de Lure. LŌĆÖ├®cole is translated here as school, but it has more the meaning of a school of thought than a formal educational body.

So much of an event has this annual gathering become that its organization is no longer left to individuals. It is now the responsibility of Les Compagnons de Lure, a society registered under French law, devoted to a living doctrine of typography based on the Latin conception and paying special attention to new methods of printing, particularly photographic composition (or filmsetting). Maximilien Vox is the chancellor, Robert Ranc is the president, and the secretary general is Pierre Lamaison, publisher, gastronomic expert, and poet.

There are three reasons for the growing importance of LŌĆÖ├ēcole de Lure. One is the quality and standing of its members, which ensure that the results of its discussions are effective at a high level. The second is its growing international character. Although the French are sometimes accused of being more insular than the British (and, indeed, the schoolŌĆÖs discussions are held not only in the French language but in a French atmosphere), the French practitioners in the graphic arts are strongly conscious of the international importance of those arts and welcome the growing participation in LŌĆÖ├ēcole of people from other countries. Those participants from overseas have returned to their homes, their work refreshed with the French joie-de-vivre (which is particularly manifest at the schoolŌĆÖs more informal functions), and ready to apply themselves to the development and application of the schoolŌĆÖs ideas.

The third reason follows from that. LŌĆÖ├ēcole de Lure is the only group of its kind in the world meeting regularly to develop and departing separately to put into practice a definite set of ideas concerned with the principles of the callings its members follow. Basically the school stands for the propagation of une graphie latine. ŌĆśLatinityŌĆÖ is not a synonym for ŌĆśMediterranianismŌĆÖ, but is rather considered as the Renaissance-classical approach to the printed word. Just as the writers, artists, and printers of the Renaissance sought their inspiration in the letter forms of the Carolingian era and the earlier Roman letter cutters, the Lurs group today, with the possibility of vast quantities of ŌĆślettersŌĆÖ becoming available through the medium of filmsetting, take, as it were, a cultural stand for the Roman ideal.

Filmsetting will liberate printing from its metal prison, but the result may revive the truism ŌĆśLiberty, what crimes are committed in thy nameŌĆÖ. The discipline of type cutting did not stop the production of typographical horrors and the easier medium of film will even more encourage the tasteless. It is realized that time cannot stand still and that there must be novelty and change. But this should be within a cultural framework. It is significant that one of the world’s most experimental type designers, Roger Excoffon, is a regular compagnon of LŌĆÖ├ēcole de Lure. He is the creator of Mistral, a script which is not a technical tour-de-force but remarkably pleasing to the eye.

It is thought, not without reason, that the Roman alphabet is not only the most beautiful in conception but also the most efficient. If those nations now approaching manhood wish to educate their peoples they will, it is felt, have to discard the earlier, more primitive methods of indicating sounds in print and adopt the Latin approach. This is not an idealistic or impractical notion. Kemal Ataturk made the Roman alphabet compulsory for modern Turkey, and the rulers of China, after much hesitation, have now adopted an experimental Roman-style alphabet.

Again, the flexibility of the Roman alphabet, its richness, variety, and clarity have not been lost on those who in the past have leaned on variants or on other forms of transmitting the language. The Germans are gradually dropping what is known in Britain as the black-letter, and a classic school of type designing is in the ascendant in Germany. The Russians are finding that Cyrillic has its draw-backs and it is clear that a very subtle, but nevertheless noticeable influence is being exercised by those nations within the Russian sphere who use the Roman alphabet ŌĆö the Poles, Czechs, Latvians, and Lithuanians. Too much can be made of this, but the tendency is there.

But latinity means more than the Roman alphabet. It means the classic approach to art, and to life itself, in contrast with the ŌĆśfunctionalŌĆÖ school of thought. It supports decoration, experiment, and vivacity in printing and all its allied forms. It is opposed to the dull, the over-precise, the pedantic, the puritanical, the heavily Teutonic, and the shoddy.

Discussions at the five gatherings at Lurs have ranged widely. The members of the group have found that clearly to convey their principles demands, first, a common technical language. It is here that one of the most outstanding successes of the school can be noted. Maximilien Vox, long conscious of the contradictions in both the Anglo-Saxon and French methods of type classification, made the production of a new classification one of the schoolŌĆÖs projects. It took some time, many discussions, a number of alterations, but eventually the Vox classification, based on the ŌĆśbiologicalŌĆÖ origin of a type face, was born.

The Vox classification of nine groups ŌĆö Manuaires, Humanes, Garaldes, R├®ales, Didones, M├®canes, Lin├®ales, Incises, and Scriptes ŌĆö has been sufficiently described elsewhere. Who can say whether it is the best possible classification, or for all time? It has been criticized because of the names which have been adopted. Can they be translated into all languages? Does it matter? Vox himself has said that it is the groupings which count, not the names. It should not be difficult to select, or to evolve, appropriate names in various languages. Another point made is that all possible type faces cannot be fitted into the groups. Vox replies: make sub-groups by using two or more names. Eventually any kind of type will become clear by this method. Whatever the criticisms the classification works and, like LŌĆÖ├ēcole de Lure, it has no real rivals.

This typographic classification has been adopted or is in the process of being adopted for catalogues; in France, of Deberny et Peignot, the Olive typefoundry, the printers Mame et Coulouma, and the blockmakers and typesetters Clich├®s Union; in Holland by Typefoundry Amsterdam; in Italy by the Nebiolo typefoundry; in Spain by Sadag; in New York by the Photo-Lettering organization, perhaps the biggest of its kind in the world. It was introduced to a bigger and more widely international audience when John Dreyfus used it as the basis of his book Conspectus Typorum, presented to all delegates of the 1957 International Master PrintersŌĆÖ Congress in Lausanne.

No doubt the system will be adopted by the various printing industries and by the schools. Its use in the catalogues of such organizations as Clich├®s Union and Photo-Lettering will lead to its becoming part of the language of the advertising and publicity professions, who are often the arbiters of typographical matters. No longer in Britain will a type face originating in the eighteenth century be called ŌĆśmodernŌĆÖ; no longer will there be confusion between the┬ĀŌĆśgothicŌĆÖ of America and that of Britain. The Vox classification clears up the matter.

Punctuation marks were a problem discussed last year at LŌĆÖ├ēcole de Lure. English, German, French, and Spanish ideas differ, so the school has adopted as a project the rationalization of punctuation. This may mean that such ideas as the Spanish exclamation and interrogation marks will be universally adopted. Inverted commas, too, caused comment. The English method seemed the most unobtrusive and may be universally acceptable. The lack of unity in French typographical regulations in France, Belgium, and French-speaking Switzerland was also stressed, and the proposal was made that the matter be referred to UNESCO. UNESCO may refer the matter back to LŌĆÖ├ēcole de Lure as the best body to deal with the problem.

Confusion over technical terms has also hampered the compagnons so another project may concern the rationalization of printing terms. This would not cut across the excellent work of Rudolf Hostettler who has compiled a dictionary of printersŌĆÖ terms in five languages. What is sought is an end to the confusion caused, for example, by the word ŌĆśoffsetŌĆÖ which has become synonymous with ŌĆślithographyŌĆÖ, although any printing process can be ŌĆśoff-setŌĆÖ. Such anomalies as ŌĆśdry offsetŌĆÖ could then be considered in their true perspective. This problem might be thought to be the task of various institutions devoted to standardization, but since there is little activity in that direction it is probable that there might be another ŌĆśclassificationŌĆÖ emanating from Lurs.

Other, more local, enterprises are under way. For example Marius P├®raudeau, another regular compagnon, who has been behind the French papermaking organization La Feuille Blanche and who founded the museum of paper at the old papermaking mill of Richard de Bas, is preparing a museum of printing for Lurs. As a result of the schoolŌĆÖs activities a water supply system is being laid on at Lurs ŌĆö a remarkable event for a practically ruined village which was once in danger of being abandoned altogether.

If eventually more lively forms of typography and decoration in printing become more popular, if better taste prevails in printed production, if drainpipe functionalism and deadpan British formalism succumb to Latin joie-de-vivre, if the Roman alphabet is adopted in many parts of the world, if British children begin to use Spanish punctuation and Italian printers English quotation marks, if we all begin to talk a rational technical language so that ŌĆśdry offsetŌĆÖ becomes ŌĆśletterpress offsetŌĆÖ and ŌĆśBuchdruckŌĆÖ really does mean ŌĆśbook printingŌĆÖ, then a great deal of credit must go to the small band of pioneers led by Vox, Giono, Ranc, and Garcia, who each year meet in that remote spot in Provence.

{JM}